Grawlixes [1], also called maladicta [2] or obscenicons [3][4], are a set of polymorphic graphemes that together constitute a pseudo-script commonly employed in comic strips, as well as other forms of cartooning that make use of speech balloons or other fumetti [5] to artfully represent expletives and inappropriate language without running afoul of editorial censorship.

Grawlixes were initially characterized by the U.S.-born comic strip artist Mort Walker in 1964 in correspondence with the National Cartoonist's Society entitled "Let's Get Down to Grawlixes". The nature of this correspondence is not clear as it was variously characterized by Walker as "a rather pedantic presentation" [6] or "an article for [a] magazine" [7]. Keith Houston has indicated that the word or article in question may have found its way into print in the January 1969 issue of The Cartoonist, the magazine of the National Cartoonist's Society, at the very latest [8].

Regardless of whether or not this article marked the first non-private use of the term, the term grawlix had certainly been used outside of cartoonist circles no later than Walker's 1975 book Backstage at the Strips in which the previous correspondence was first referenced, even if it did not clearly indicate what jarns, quimps, nittles and grawlixes were. It was only in his 1980 Lexicon of Comicana that the set of graphemes was clearly characterized in a work available to the general public, using both the term maladicta [2] and grawlix [1] interchangeably to refer to sequences of graphemes consisting of those encoded in this proposal. The term grawlix was additionally used to characterize a specific grapheme consisting of an irregular thick black squiggle of varying lengths.

Since its initial technical definition by Walker, the lexical scope of the term grawlix has been broadened from both of these meanings to refer more popularly to any string of characters used by an author to obscure an expletive or other inappropriate language, including strings of punctuation characters in the Basic Latin block like those in the string !@#$%&*?, leading to additional confusion among researchers [8].

Due to the difficulty in distinguishing these three senses of the term grawlix, for the remainder of this proposal the term obscenicon will be used to refer to a single grapheme to be encoded, in accordance with this proposal, by a single Unicode codepoint. Maladicta will be employed to refer to any string of codepoints or characters that, when printed, might otherwise be popularly called a grawlix, whether encoded in accordance with this proposal, or as a string of Unicode punctuation codepoints and other symbols. The term grawlix will refer exclusively to the distinct obscenicon ("grawlix proper") when specified in lowercase, except when clearly used as the name of this proposed block allocation and encoding due to popular usage of the term ("Grawlix codepoints", "Grawlix encoding").

It is important to note that this proposal does not seek to address the broadest sense of maladicta and their encoding in Unicode. The reasons for accepting legacy compatibility forms that encode maladicta using literal punctuation and symbol codepoints for the indefinite future are multitude and will not be detailed here. The encoding proposed below primarily seeks to support the study of maladicta within the broader field of comic strip art and lettering from a critical and analytical standpoint and to support the implementation of digital typefaces for comic lettering that may make take advantage of the polymorphic formulation of maladicta first characterized by Walker. This encoding does not intend to supplant alternate methods of representing such strings of text using codepoints outside of this encoding.

Individual obscenicons are characterized by Walker in a polymorphic sense, which is to say that a single obscenicon may be represented by any number of stylized glyphs in the same hand, which may differ even within the same string of text. Indeed, in their research into the history of maladicta in comic strips in the United States, Gwillim Law has uncovered numerous examples of maladicta dating to the mid-1920s in which multiple distinct nittles and quimps are used in a single string of text [9]. This proposal seeks to support this analysis by assigning each symbolically distinct obscenicon a codepoint, so as to distinguish an abstract obscenicon from its concrete, realized glyph in a given hand and location within a work.

In other words, the selection of a particular glyph for a given codepoint in this encoding may be random, pseudo-random, fully deterministic, or even left to the aesthetic whims of the user, but the decision to choose one given obscenicon over another when deciding their sequence may be less so, and is the subject of this encoding as a result.

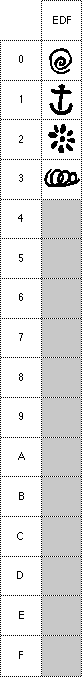

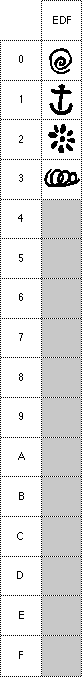

This proposal currently encompasses the four obscenicons identified by Walker in The Lexicon of Comicana:

Limited research has been done into the development and characterization of maladicta outside the United States, aside from the limited collection of French maladicta gathered by Law [9]. Proper characterization of obscenicons in non-English contexts may require the allocation of additional codepoints in this range (such as to represent the "Pseudo-Chinese characters" Law mentions as being common in French contexts).

In addition, the extension of the term grawlix to encompass maladicta that use Basic Latin punctuation and symbols has led to an increase in the use of such punctuation and symbols for such in comic strips themselves. Many of the samples gathered by Law from newer strips starting in the late 1990s ("The Boondocks", "Get Fuzzy", "Candorville") feature few, if any, quimps, nittles, and grawlixes (proper) in their maladicta, and what few jarns exist in these samples might be better identified as U+0040 COMMERCIAL AT. It is thus possible that the rise in use of such characters (or a deeper study of early 20th century maladicta) may require characterizing a new obscenicon (and therefore allocation of an additional codepoint) to cover certain forms of "standard" punctuation and symbols not hitherto described by Walker that have nevertheless become intrinsically linked to the pseudo-script.

The polymorphic nature of obscenicons means that fonts that attempt to generate a deterministic pseudo-random sequence of glyphs for these obscenicons may inadvertently reveal the contents of nearby, potentially deliberately obscured text if the pseudo-random seed used for selecting glyphs is poorly chosen. Care must be taken to ensure that the selection of any seed used for the pseudo-random selection of a glyph to represent a codepoint in the Grawlix block does not unnecessarily reveal the contents of nearby text, ideally making their method of glyph selection as clear to end-users as possible.

Implementors seeking to render a diverse set of glyphs from a codepoint string containing multiple instances of the same obscenicon are strongly encouraged to seed pseudo-random glyph selection only from the presence and order of consecutive obscenicon codepoints, in order to balance the need for pseudo-random glyph selection with the predictability of glyph rendering when text is changed elsewhere in a document. It is also strongly encouraged to allow end-users to directly control the display of such alternate glyphs through the use of OpenType stylistic alternates, stylistic sets and character variants using the salt, ss## and cv## OpenType features.

In addition to the above, the similarity of these obscenicons to extant codepoints should be considered when evaluating the risk of homograph attacks involving any of the pseudo-characters in the Grawlix block. (Compare the jarn to U+1F300 CYCLONE, or the nittle to U+002A ASTERISK or any of the asterisks or star codepoints in the Unicode Dingbats block.) It is therefore strongly recommended that web browser vendors and domain name registries that choose to respect this UCSUR allocation exercise appropriate caution to avoid homograph attacks, such as by always rendering characters in this range as Punicode, by refusing to allow the Punicode encodings of all strings containing codepoints in this range to be registered, or by any other reasonable means already employed by such vendors and registries to protect against homograph attacks.

U+EDF0 JARN

U+EDF1 QUIMP

U+EDF2 NITTLE

U+EDF3 GRAWLIX

U+EDF4 (This position shall not be used)

U+EDF5 (This position shall not be used)

U+EDF6 (This position shall not be used)

U+EDF7 (This position shall not be used)

U+EDF8 (This position shall not be used)

U+EDF9 (This position shall not be used)

U+EDFA (This position shall not be used)

U+EDFB (This position shall not be used)

U+EDFC (This position shall not be used)

U+EDFD (This position shall not be used)

U+EDFE (This position shall not be used)

U+EDFF (This position shall not be used)

[1] a b Mort Walker, The Lexicon of Comicana (Port Chester, N.Y.: Museum of Cartoon Art, 1980), front cover.

[3] Benjamin Zimmer, "Obscenicons in the Workspace," Language Log (24 August 2006): http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/003500.html, accessed 27 February 2023.

[4] Benjamin Zimmer, "Obscenicons a century ago," Language Log (17 July 2010): https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2457, accessed 27 February 2023.

[5] Walker, Lexicon, 38–39.

[6] a b Mort Walker, Backstage at the Strips (A&W Visual Library, 1975), 26–31

[7] Walker, Lexicon, back cover.

[8] a b Keith Houston, "Miscellany № 90: 🌀🪐☆✻, or, the grawlix," Shady Characters (29 April 2021): https://shadycharacters.co.uk/2021/04/miscellany-90-grawlix/, accessed 27 February 2023.

[9] a b Gwillim Law, "Grawlixes Past and Present," (19 July 2010): http://www.statoids.com/comicana/grawlist.html, accessed 27 February 2023.

[10] Walker, Lexicon, 28.